NovelFoundry Database Structured For Day 0 and Day 1000

On Day 0 my constraints are shipping fast and learn as I go. But come Day 1000 I don’t want to be held hostage by a design that assumes 50 users forever. So every choice below is simple enough for now, but compatible with sharding/partitioning later.

Design Decisions

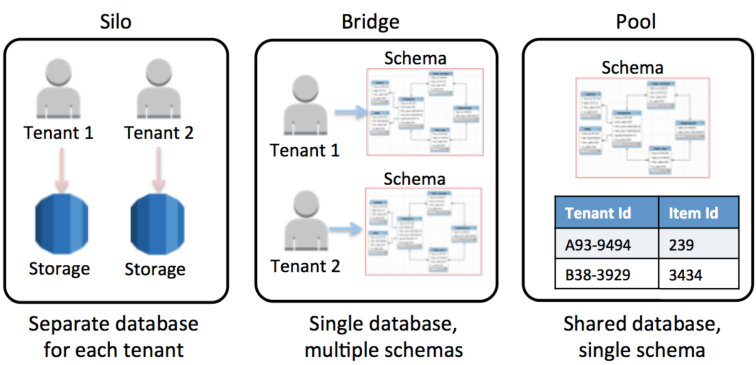

My original thought had been to use an operations database and link to a user database, where all the sensitive data per user would be stored. However, upon reading further and realizing that this design would quickly become unmanageable once I surpass my alpha team of 50 users, it became apparent that the best course of action was to use a pool database structure instead of a silo approach.

Database Separation

Upon reading Designing your SaaS Database for Scale with Postgres, Designing Your Postgres Database for Multi-tenancy, and skimming F1: A Distributed SQL Database That Scales, I was convinced that “Have all tenants share the same table(s)"1 was the best course of action to follow.

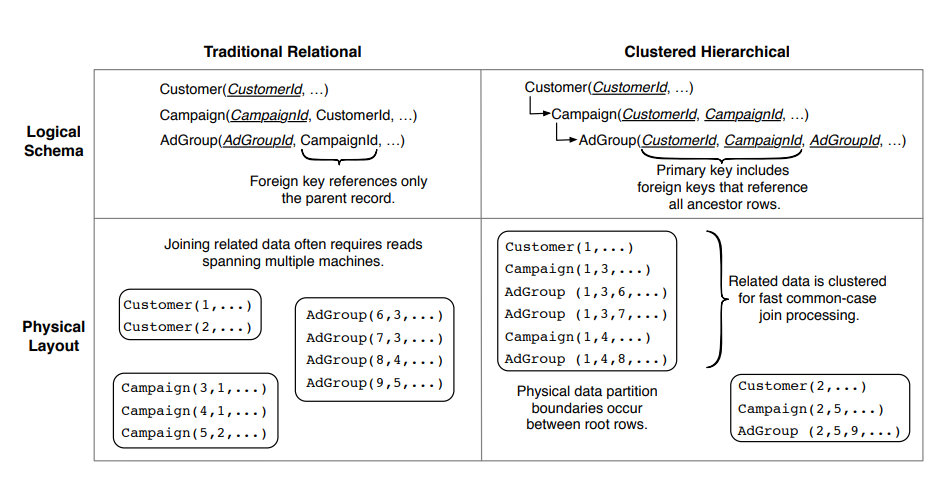

Traditional Relational Schema vs Clustered Hierarchical Schema

Source: 2

Source: 2

I understood the basics of what I wanted, to allow for scaling up to thousands of users without bogging myself down and creating myself a job as a database admin. However, I still needed more reading, as I’d yet to fully visualize what my database would look like. (Most of my experience has been with phpMyAdmin; love GUI visualization of the data. Mostly because that’s what NameCheap uses as their default database manager.)

Upon reading SaaS Storage Strategies: Building a multitenant storage model on AWS in its entirety, I fully understood the tradeoffs I was making and more importantly, I could visualize in my mind’s eye what the data would like for my entire SaaS. Better yet, I could visualize how it would scale with users, and I started thinking less in terms of “one big Postgres box” and more in terms of “how do I refactor this into a distributed system later?”

That’s where the Citus Documentation comes in. Citus is not some magic feature that every managed Postgres gives you for free—it’s a Postgres extension. If NovelFoundry ever outgrows a single Postgres instance, the realistic paths are: self-host Postgres + Citus, or move to a provider that exposes Citus (Azure Cosmos DB for PostgreSQL, Crunchy, etc.). In both cases, the thing that makes the migration boring instead of terrifying is the schema design I choose now.

So I’m deliberately designing around a clear distribution key: tenant_id. Every tenant-scoped table gets a tenant_id column, and all the “hot path” queries are written to be strongly tenant-scoped (WHERE tenant_id = $1 AND ...) instead of doing cross-tenant joins. That way, if/when I need Citus, I can say “distribute this table by tenant_id” and let it shard cleanly, instead of trying to retrofit multi-tenancy onto a schema that never planned for it.

Citus is an open source extension to PostgreSQL that transforms Postgres into a distributed database. To scale out Postgres horizontally, Citus employs distributed tables, reference tables, and a distributed SQL query engine. The query engine parallelizes SQL queries across multiple servers in a database cluster to deliver dramatically improved query response times, even for data-intensive applications. 4

Database Portioning Models

Source: 7

Source: 7

I’ve chosen to use the pool model for ease of scalability, as my users will be uniform in their use case, only differing in the amount of disk space they take up. Every tenant row lives in the same table. There’s a tenant_id column on all tenant-scoped tables. RLS (Row Level Security) is doing the isolation work instead of siloing the user’s data into it’s own database.

Self-Hosted vs Managed

Originally I had planned to use Supabase as their free tier was generous and the $25/month plan was quite reasonable for my needs, and once I outgrow that tier the price could be reevaluated, as it would require fulltime staff to manage the SaaS at that point. Then I looked into hostinger VPS and decided to go that route and self-host my postgreSQL database on the same virtual machine as my backend.

File Storage

However, once I realized that future features are going to require larger storage space per user, the best option becomes object storage (S3-compatible). Only then I need to handle my own setup and security between the database and S3, or I could go back to Supabase and let them handle it (and take advantage of the first 1GB free, enough to handle the 50 member alpha team).

Also as I dug deeper into authentication, storage needs for backups, alerts, and more… I decided that it was a no brainer. I’ll gladly pay $25/month, even if I could host and scale it on my backend server to start, if it’ll save me hours of maintenance. (Not trying to make myself jobs for no reason.)

Between the 100gb from Hostinger and the 100gb for Supabase, I should be set for a long time. And if not, that’s a problem I’ll gladly embrace. Supabase: 8 GB Postgres disk for row data, plus 100 GB S3-style object storage. Hostinger’s 100 GB is for my app server and logs, not user uploads.

Final Design

Supabase owns the data plane (Postgres + RLS, Auth, S3-compatible storage). Hostinger runs the backend app plane (API + worker jobs), while the marketing site itself lives on Namecheap. This keeps all the multi-tenant complexity in one managed Postgres + storage stack, and if I ever move off Supabase it’s still a single data migration instead of three different systems to unwind.

Next Steps

On Day 0, I just need something my alpha team can actually use without me babysitting the database every night.

On Day 1000, I want to look back at this schema and not curse myself.

1) Lock in the tenant-aware schema.

- Add a

tenant_idcolumn to every table that holds tenant data (projects,manuscripts,analyses,billing_events, etc.). - Standardize my primary keys so they play nicely with clustering/sharding later

(tenant_id, project_id, analysis_id).

2) Turn on Row Level Security and try to break it.

- Enable RLS on the core tables and write the minimal “tenant can only see its own rows” policies.

- Tie those policies to Supabase Auth so that a single JWT maps cleanly to a

tenant_id.

3) Shape the storage layout.

- Create a Supabase Storage bucket with a predictable path scheme:

tenant_id/user_id/project_id/<file-type>/<filename>. - Wire up signed URLs and expirations so the API never has to stream big documents through the app server unless absolutely necessary.

4) Write down the “roadmap” for Day 1000.

- Document what a migration to Citus would roughly look like: which tables become distributed, which stay as reference tables, what the distribution key is (

tenant_id), and what downtime constraints I care about. - I don’t need to do this yet, but I want a one-page note that proves the current design can evolve instead of trapping me.

Once those pieces are in place, I’ll feel good about inviting more than 50 people into NovelFoundry without secretly worrying that one power user is going to set my little forge on fire.

Sources

- Designing your SaaS Database for Scale with Postgres

- F1: A Distributed SQL Database That Scales

- Designing Your Postgres Database for Multi-tenancy

- Citus Documentation

- Row-level security recommendations

- Multi-tenant data isolation with PostgreSQL Row Level Security

- SaaS Storage Strategies: Building a multitenant storage model on AWS