NovelFoundry Backend: NGINX, Celery, Redis

This is a continuation of the build out documentation. My last entry was NovelFoundry Database Structured For Day 0 and Day 1000 where I worked through the choices that led me to Supabase as my database host, instead of running Postgres myself on another Hostinger VPS.

Now of course, all technical decisions can be altered later (and if I’m being honest, they will be). But I see no reason not to use Supabase for a long time; the free tier will 100% cover the alpha phase, and it’ll likely get us through beta too.

You can also read the entire journey via the NovelFoundry tag.

On Day 0 my constraints are shipping fast and learning as I go. But come Day 1000 I don’t want to be held hostage by a design that assumes “one user, one request, one response” forever. With NovelFoundry specifically, the hard truth is this:

A lot of the work doesn’t fit inside a normal web request.

Some tasks are quick. Others are “upload manuscript → parse → chunk → run analysis pipeline → generate exports” and that is not something I’m going to pretend is a cute little 200ms API call.

So this build log is me locking in the backend shape that makes Day 0 usable and makes Day 1000 a scaling exercise instead of a rewrite.

Broad Strokes Overview

NGINX, Celery, and Redis are all new technologies to me; which means lots of reading this week. Thursday was a no-work day, Thanksgiving with extended family, but now I’m back at it.

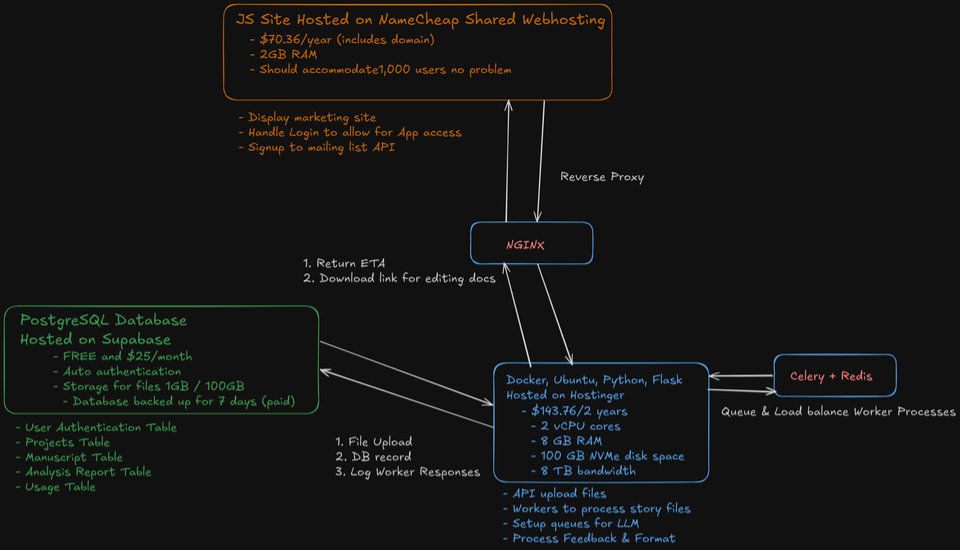

Here’s the mental model I’m aiming for:

- Supabase as the data plane: Postgres with RLS (Row Level Security), Auth, and S3-style object storage.

- Hostinger VPS as the app plane: the API and background workers that do the slow work.

- NGINX: reverse proxy and load balancer.

- Celery: anything slow or failure-prone becomes a task instead of a web request.

- Redis: Celery’s broker, plus some future caching.

The request flow looks like this:

- User clicks Analyze

- API validates tenant + permissions (JWT → tenant context)

- API creates an

analysis_jobrow in Postgres and immediately returns ajob_id - API enqueues a Celery task with IDs/pointers, not giant payloads

- Worker runs the slow work; updates job status/progress; writes artifacts to Supabase Storage

- Frontend polls job status (or later I can push an update stream), then displays results

Core Design Decision

Keep HTTP Fast, and move the Slow Work Elsewhere. In the SaaS designs I’ve seen, they do the work within the API request, and if there is a connection issue, the process can just be reran. NovelFoundry is not that kind of SaaS.

- LLM calls are slow; especially once they’re all chained together.

- Document parsing can be slow.

- Pipelines are multi-step.

- Failures happen (timeouts, rate limits, etc…).

Users don’t care why it’s slow. If it feels broken, then the software is a failure. With total processing times in excess of 30 minutes for a modest sized novels, there’s no way to handle the user requests instantly, and streaming the LLM responses won’t make sense given the multi-step-processing required to offer a comprehensive story analysis.

So I’m designing the system so that the API stays responsive while the heavy lifting happens as queued jobs.

The important detail here (and this is one of those “learn it early or suffer later” moments): Redis is not where “truth” lives. Redis moves small messages quickly. Celery’s own docs say Redis works well as a broker for “rapid transport of small messages,” and that large messages can congest the system. Source: 1

So the rule is:

Celery tasks get IDs and pointers. Postgres + Storage hold the real data.

If a task needs the manuscript, it fetches it from Storage (or reads it from the database if it’s already normalized text). If it needs to update state, it writes to Postgres.

NGINX

I’m presently working my way through: NGINX Handbook by Farhan Hasin Chowdhury, a free guide courtesy of Free Code Camp (very grateful for the “here’s how it works, no fluff” approach).

NGINX Day 0

On Day 0, NGINX is my reverse proxy: one public entry point for the backend, with the app sitting safely behind it. NGINX’s own docs describe the basic reverse proxy setup as “pass a request from NGINX to proxied servers,” plus header control and response buffering. Source: 3

This lets me centralize the boring-but-critical things:

- TLS termination (Let’s Encrypt)

- sane header handling

- request size limits (uploads are a real thing for NovelFoundry)

- timeouts that are appropriate for an API that enqueues work instead of doing it inline

Day 0 goal: the user never experiences a “request timed out” just because the work is slow. If the work is slow, the response should still be fast.

NGINX Day 1000

This is where NGINX stops being “just the front door” and becomes the thing that keeps the backend simple as I grow.

NGINX can load balance traffic across multiple backend servers by defining an upstream group and proxying requests to that pool. The practical win is huge: when I need a second (or third) API instance, I don’t redesign my architecture—I add another server to the upstream list and keep moving.

Load balancing across multiple application instances is a commonly used technique for optimizing resource utilization, maximizing throughput, reducing latency, and ensuring fault‑tolerant configurations. Source: 4

Day 1000 looks like this:

- multiple API instances (same codebase, horizontally scaled)

- NGINX spreads requests across them

- the API stays stateless (Supabase holds state)

- workers scale independently (more jobs require more workers, not more API complexity)

That’s the scalable design I’m after ; growth as config changes, not a rewrite.

Celery

Why Celery exists in NovelFoundry

Celery is how I keep the API fast while the real work happens in the background.

NovelFoundry has tasks that take seconds to minutes (file parsing, chunking, multi-step analysis pipelines). If I try to run those inside a normal HTTP request, I’m basically begging for:

- timeouts

- duplicated work (because users refresh or clients retry)

- a brittle UX that “feels broken” even when it isn’t

- and eventually me debugging production at 3 AM because someone uploaded a cursed

.docx

Celery fixes that by turning slow work into jobs with a lifecycle:

- queued

- started

- progress updates

- success / failure

- retries when it makes sense

Under the hood, Celery splits responsibilities cleanly: a broker transports tasks from the API to the workers, and a result backend can store task state/results so they can be retrieved later. Redis can be used for either role (or both).

Celery has the ability to communicate and store with many different backends (Result Stores) and brokers (Message Transports). Source: 1

Celery Design

- Producer: the API (it creates the job row; then enqueues work)

- Broker: Redis (it transports the task messages)

- Workers: Celery workers (they execute the slow pipeline steps)

- System of record: Supabase Postgres (job status, progress, errors, output metadata)

- Artifacts: Supabase Storage (uploads + generated exports)

The key constraint is message size. Celery’s docs say it plainly:

As a Broker: Redis works well for rapid transport of small messages. Large messages can congest the system. Source: 1

So I treat Redis like a conveyor belt for pointers, not a freight train for payloads.

A task payload should look like:

tenant_idproject_idmanuscript_idanalysis_job_id- maybe a couple flags (which pipeline steps are enabled)

Not:

- the entire manuscript text

- giant chunk arrays

- anything I don’t want clogging the conveyor belt when traffic spikes

Task Design

These are the obvious Day 0 job types for NovelFoundry:

- Ingestion

- upload → parse (DOCX/PDF) → normalized text

- chunking chapters/sections

- Analysis pipeline

- beat sheet analysis

- global editorial letter generation

- chapter-level feedback

- Exports

- generate markdown/PDF outputs

- bundle results

- Maintenance

- cleanup temp artifacts

- expire signed URLs

- (later) scheduled jobs and backfills

Anything that could take long enough to annoy a user becomes a job. Anything that’s likely to fail transiently becomes a job. Anything that I might want to scale independently becomes a job.

Guardrails

On Day 0 I’m building guardrails that prevent the classic queue disasters:

- Idempotency: a retry should not create duplicate rows or outputs.

- Time limits: runaway jobs get cut off; they don’t run forever.

- Backpressure: if I have 2 workers, the queue grows; the API still stays responsive.

Day 1000, this extends into routing queues by workload type (CPU-ish parsing vs network-ish LLM calls), tenant fairness, and more sophistication. But Day 0 just needs the bones in place.

Redis

Redis is here because it’s good at moving small messages quickly, and Celery supports Redis as a broker and as a result backend.

What Redis is (in my system)

- Primary role: Celery broker (task transport)

- Optional role: Celery result backend

- Future role: lightweight caching

What Redis is NOT (in my system)

Redis is not where I store anything I can’t afford to lose.

It’s not my audit log.

It’s not my system of record.

It’s not the canonical source of truth for “what happened” in NovelFoundry.

The cleanest example is Redis Pub/Sub. Redis’ docs are very explicit:

Redis’ Pub/Sub exhibits at-most-once message delivery semantics. As the name suggests, it means that a message will be delivered once if at all. Once the message is sent by the Redis server, there’s no chance of it being sent again. If the subscriber is unable to handle the message (for example, due to an error or a network disconnect) the message is forever lost. Source: 6

So if/when I add “live progress updates,” I’m not going to pretend Pub/Sub is durable. The durable truth will still be:

- job status + errors + timestamps in Postgres

- outputs and artifacts in Storage

Supabase is still the truth layer

This is the part I’m intentionally not overcomplicating.

Supabase remains the data plane:

- Postgres tables store:

analysis_jobs(status, progress, error fields, timestamps)analysis_outputs(metadata, links to artifacts)- tenant-scoped rows with RLS enforcement

- Storage holds:

- user uploads

- generated exports

- intermediate artifacts (if I keep them)

Redis coordinates work. Supabase remembers what happened.

That separation is what keeps Day 1000 sane.

Failure Modes

This section is basically “what happens when things go sideways,” because pretending failures don’t exist is how you end up miserable.

- Worker dies mid-job

- job stays “in progress” until a timeout watchdog marks it stale / failed

- rerun safely via idempotency key

- Redis restarts

- queued tasks may be lost depending on configuration; do not treat the broker as the ledger

- Postgres job rows still exist; API can re-enqueue based on job state if needed

- OpenAI/API timeouts

- retry with backoff on transient failures

- fail fast (and loudly) on non-transient failures; store the error message in

analysis_jobs

- User refreshes 10 times

- the API should never duplicate work; it should reference the same

job_id

- the API should never duplicate work; it should reference the same

NovelFoundry can be magical, but the backend should be boring. This is how I keep it boring.

Failure Modes

This section is basically “what happens when things go sideways,” because pretending failures don’t exist is how you end up miserable.

The goal isn’t to eliminate every failure (we can’t). The goal is to make failures predictable, recoverable, and non-destructive. If a job dies, I want to know where it died, what the user should see, and how I can safely retry without duplicating work or corrupting state.

So here are the main ways this system can break—and what “boring” looks like in each case.

1) Worker dies mid-job

This one is inevitable. Workers crash. Deploys happen. One weird document hits a parser edge-case and takes the process with it.

What I expect to happen:

- The job is marked

in_progressin Postgres. - The worker starts running the task.

- Then the worker disappears before it can mark completion.

What I do NOT want:

- The job stuck in

in_progressforever. - The user staring at “loading…” with no explanation.

- A retry that creates duplicate outputs because it can’t tell whether it already ran.

My “boring backend” response:

- Jobs have timestamps (

started_at,updated_at, etc.). - A watchdog (either a periodic task or a scheduled check) marks jobs as stale if they haven’t updated progress in a reasonable window.

- e.g., “if

status = in_progressandupdated_atis older than X minutes, mark asfailed_stale(orneeds_retry).”

- e.g., “if

- Retries happen safely via an idempotency key, so rerunning the task doesn’t create duplicate artifacts or duplicate rows.

- The idempotency key might be

(tenant_id, manuscript_id, analysis_version)or similar. - The important part is: the worker can look at Postgres and say “this job already produced outputs; don’t do it twice.”

- The idempotency key might be

In other words: a worker dying should be annoying; it should not be catastrophic.

2) Redis restarts

Redis is my broker. It’s the conveyor belt for tasks. And like any conveyor belt, if it shuts off, the factory can’t move work around.

What can happen:

- Enqueued tasks might temporarily stop moving.

- Some queued tasks might be lost depending on how Redis persistence is configured (and how Celery is configured).

- Workers might reconnect and continue, or they might fail tasks and retry later.

What I do NOT want:

- Redis implicitly becoming my “truth layer” without me realizing it.

- Losing track of jobs just because the broker restarted.

My “boring backend” response:

- Postgres is the ledger. Redis is not.

- The moment the API creates a job, it writes a durable row in Postgres (that row exists even if Redis is having a bad day).

- If Redis restarts and a message is lost, I can recover because Postgres still knows:

- which jobs exist

- what state they’re in

- whether they completed

- whether they need retry

This makes recovery possible in the simplest way:

- If a job exists in Postgres as

queued(orin_progressbut stale), the API or a watchdog can re-enqueue it.

That’s the theme: I can lose the message and still not lose the story, because the ledger is elsewhere.

3) External API timeouts/rate limits

This is the failure mode that will happen the most, because it’s outside my control. Sometimes the model is slow. Sometimes I hit a rate limit. Sometimes the network just shrugs.

I treat these failures as two categories:

A) Transient failures (retryable)

Examples:

- timeouts

- 429 (rate limited)

- 502/503 type responses

- network hiccups

My response:

- retry with exponential backoff

- cap retries so one job doesn’t hammer an API forever

- log the error details (for me)

- store a user-readable summary in

analysis_jobs(for them)

The goal is: the system has patience, but not infinite patience.

B) Non-transient failures (not retryable)

Examples:

- invalid input (corrupt file that can’t be parsed)

- prompt/validation errors

- deterministic failures that won’t improve with time

My response:

- fail fast (and loudly)

- store the error message in

analysis_jobs - stop retrying, because retrying would just waste money and time

The overarching principle is: retries are a tool for reliability, not a tool for denial.

4) User refreshes 10 times (or clicks Analyze twice)

This is less of a “system failure” and more of a “user behavior reality.” People double-click. People refresh. People lose patience.

What I do NOT want:

- duplicate jobs for the same work

- duplicated charges (eventually)

- duplicated outputs cluttering Storage

My “boring backend” response:

- the API should be able to say: “this work already exists.”

- the frontend should display the same job when the same analysis is requested.

In practice, that means:

- create a

job_idonce - reuse it for polling and retrieval

- protect the creation endpoint with idempotency so repeated requests return the existing job instead of spawning a new one

This creates a very unsexy but very important property: the system is safe under impatience.

5) Partial progress (the job succeeds… except it didn’t)

This is the subtle one: the worker runs 80% of the pipeline, writes some outputs, then fails on step 9.

If I’m not careful, this creates the worst debugging experience:

- some artifacts exist

- some rows exist

- the job is “failed”

- reruns either duplicate or overwrite inconsistently

My “boring backend” response:

- treat each pipeline step as explicit state:

queued → ingesting → parsing → chunking → analyzing → exporting → complete

- store progress in Postgres as a single source of truth

- on retry, decide whether to:

- resume from the last completed stage, or

- restart cleanly and overwrite/cleanup consistently

For Day 0, I may restart cleanly (simpler). For Day 1000, resuming becomes worth it (more complex, but more efficient).

NovelFoundry can be magical, but the backend should be boring.

Failures should be:

- visible (in

analysis_jobs) - explainable (errors stored with context)

- recoverable (retry safely)

- non-duplicating (idempotency everywhere it matters)

This is how I keep the forge from burning down when the real world shows up.

Final Design

The simplest way to describe this architecture is that I’m separating where data lives from where compute happens on purpose.

- Supabase owns the data plane: Postgres + RLS (Row Level Security) for tenant isolation, Auth for identity, and S3-compatible Storage for uploads and generated exports.

- Hostinger owns the app plane: my API (fast, stateless request handling) plus background workers (slow, failure-prone jobs like parsing, chunking, and analysis).

- NGINX is the front door: it’s a reverse proxy on Day 0, and it becomes the “make scaling boring” layer on Day 1000; because the same setup can evolve into load balancing by adding more API instances behind an upstream pool.

The point is that the user-facing API stays responsive because it doesn’t pretend slow work is “request-shaped.” It creates a job, returns a job_id, and the rest of the heavy lifting happens in the background.

Day 0: the alpha team gets a responsive app, even when the entire workflow takes 1,800 seconds.

Day 1000: I look back at this architecture and don’t regret my choices.

Next Steps

1) Stand up the queue end-to-end locally

- API creates an

analysis_jobrow and returnsjob_idimmediately (no waiting for the full pipeline). - API enqueues a Celery task with IDs/pointers only (no manuscripts, no giant payloads).

2) Make progress visible

- Worker writes progress updates to

analysis_jobsevery N seconds (or at each pipeline stage). - Frontend polls a

/jobs/{job_id}endpoint and renders “queued / running / exporting / done” instead of a spinning wheel of despair.

3) Put NGINX in front and lock in the “front door” behavior

- TLS termination

- request size limits for uploads

- sane timeouts that match the model: the API enqueues work; the workers do the work

4) Add the guardrails before I need them

- retries + backoff for transient failures (timeouts, rate limits)

- time limits for runaway jobs

- idempotency so refreshes (or double-clicks) don’t duplicate work or outputs

Once those pieces are in place, I’ll feel good about inviting more people into NovelFoundry, without worrying that one enthusiastic power user is going to set my little forge on fire.